If you think your life story would make for a page-turning novel, get inspired to submit your own manuscript by first reading Roxane Gay's Hunger, a confessional memoir about the enduring struggles she's had with her body. This new genre of book, nicknamed the femoir, focuses on the experience of people's lives that they first confess to their audience, then generalize to a universal experience. Gay does this by taking her experiences with sexual assault, eating disorders, weight, and publishing, then relating them back to the universal experiences of women of size, color, or disempowerment.

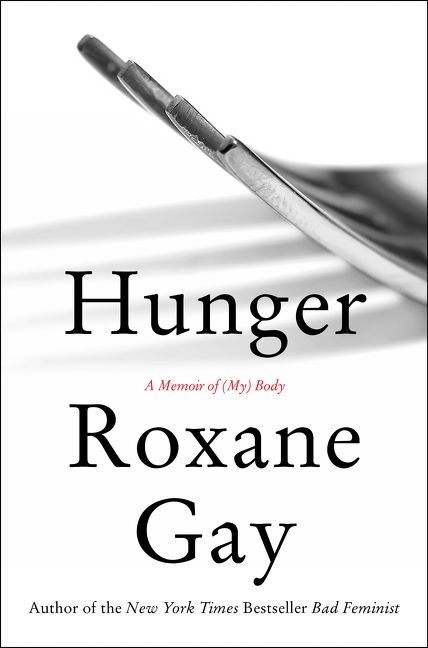

If you think your life story would make for a page-turning novel, get inspired to submit your own manuscript by first reading Roxane Gay's Hunger, a confessional memoir about the enduring struggles she's had with her body. This new genre of book, nicknamed the femoir, focuses on the experience of people's lives that they first confess to their audience, then generalize to a universal experience. Gay does this by taking her experiences with sexual assault, eating disorders, weight, and publishing, then relating them back to the universal experiences of women of size, color, or disempowerment.Roxane Gay is an author of all trades. She was a New York Times bestseller for a collection of essays titled Bad Feminist, and a finalist for the Dayton Peace Prize for her novel An Untamed State. She is a contributor to a wide array of media producers, from The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal to Buzzfeed and Bookslut. Before Roxane Gay was any of these things (author, culture maker, successful), she was a girl, daughter, and black woman in the Midwest. She was surviving, young, and insecure. These are experiences she shares with readers through a specific confessional style. Her book is widely readable, with its short sentences and piercing prose. As readers move deeper into the novel, Gay delves deeper into the complexities of her story, trusting the readers that stick with her with her darkest secrets. By trusting complete strangers with her experiences, Gay allows them to make sense of their own messy lives.

Roxane Gay opens up her femoir with a cautionary tale. This novel is not for "motivation" (Gay 2), or "strength" (Gay 3). This novel is not to inspire anyone to lose weight (Gay 2-3). Gay openly admits that this novel was difficult to write, and that the whole novel is a confession of her facing the one thing she daily tries to avoid: her body and experiences as shaped by her body (Gay 2-3). Gay sets the stage of what the reading experience is going to feel like: raw, honest, and difficult to read. She warns off readers who want the inspiration of how to love yourself, because she has not yet found that herself (Gay 3). By weeding out the readers who don't open the novel for the right reasons, Gay effectively allows herself to let down her barriers to the right people. The conversational tone of the opening, specifically, makes readers want to hear more of her story, in her own words. As readers get deeper into the novel, it is this exact tone that makes readers want to cry with Gay, empathize with her, and that makes them want to understand themselves as women and people.

However, for readers who might not share a lot of the same experiences as Gay (for example, those women who have not survived sexual assault, or who have not struggled with eating disorders), there can be difficulty connecting ot her and her specific struggles with her body. Luckily, Gay writes with such a candor about her body and herself, stating in the middle of the novel "I hate myself . . . but I also like myself" (Gay135). Such simple sentences create power in the complexity of something all women struggle with in the 21st century: self-love and their battle with self-loathing. Gay goes even further with these statements to say that she "forget[s] how to separate [her] personality . . . from [her] body" (Gay 136). This integral struggle doesn't just belong to Gay, but to all women, to all people. While not all women (and for that matter, men) will be able to relate to Gay's experiences and trauma, most can relate to the idea of hating the skin they're in while simultaneously loving who they are, all while struggling to separate the two. Such a universal mindset written with raw honesty balances Gay's personal and not-always-universal experiences.

The effectiveness of the femoir, and Hunger, lies in its deeply exposing nature. Readers feel that they know and understand Gay without ever having met her. In turn, they see their own experiences in Gay's, see themselves through her. For many women that hold similar identities or experiences, this can make them feel empowered, and seen. For other women, this style of novel can show them that they aren't alone, even if their own experiences aren't exactly reflected. Confessional memoirs like the femoir Hunger validates all kinds of women and experiences, because it allows all kinds of women to stand up and find their voices when someone else opens up the gateway for them.

*This review is also published on my Goodreads page*

Comments

Post a Comment