Jaquira Díaz was born in Puerto Rico. Her work has been published in The New York Times Style Magazine, the Guardian, Longreads, Condé Nast Traveler, and included in The Best American Essays 2016. She is the recipient of a Whiting Award, two Pushcart Prizes, an Elizabeth George Foundation grant, and fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Kenyon Review, and the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing. She splits her time between Montréal and Miami Beach with her partner, the writer Lars Horn.

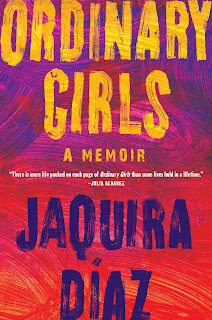

While growing up in housing projects in Puerto Rico and Miami Beach, Jaquira Díaz found herself caught between extremes. As her family split apart and her mother battled schizophrenia, she was supported by the love of her friends. As she longed for a family and home, her life was upended by violence. As she celebrated Puerto Rican culture, she couldn't find support for her developing sexual identity. Díaz writes with raw and refreshing honesty, triumphantly mapping a way out of despair toward love and hope to become her version of the girl she always wanted to be. Lyrical and searing, Ordinary Girls reads as electrically as a novel.

Our entire existence is a culmination of the stories we cannot escape. This is made abundantly clear in Jaquira Díaz's memoir, Ordinary Girls. What do we do with the stories we cannot escape? Díaz provides one answer out of many. The stories that Díaz cannot escape—namely, the Baby Lollipops murder case—shape how she defines herself. We can take stories and make them our own, allowing them space in our minds and hearts, to give them the power to change who we are, and to shape our understanding of the world.

The first time Díaz references the Baby Lollipops murder case contrasts sharply with one of the last times she does. Baby Lollipops is first " a dead toddler in the bushes, head based in, bite marks and cigarette burns all over his body" (65). As the murder case unravels, Baby Lollipops becomes "just a story on the six o'clock news" (68) to "'Toddler (unidentified)'" (70) that everyone is searching for, to, finally, "three-year-old Lázaro Figueroa" (72). Baby Lollipops' identity, in Díaz's recounting, evolves as the story changes. And it is not only Díaz's understanding of the Baby Lollipops story that changes as the details come out, but also her own understanding of her own mother. Once it is revealed that "it was [Lázaro's] mother who'd done it" (73), Díaz cannot look at her own mother the same. She finally has the language to deconstruct her mother's power to hurt her and her sister, Alaina. Once Díaz learns that Lázaro's mother killed him, she can articulate the question, "But what if that same person, the one who's supposed to love you more than anyone else in the world, the one who's supposed to protect you, is also the one who hurts you the most?" (74). Díaz's understanding of the Baby Lollipops case, and the way it permeated her childhood via the media, had the power to shape her understanding of her own mother. It gave her the power to ask a bigger question about her existence, and to understand the complex nature of people.

The Baby Lollipops case clearly takes up a lot of room in Díaz's consciousness. As she deconstructs her childhood for readers, an understanding of the Baby Lollipops case is woven through with descriptions of Díaz'z mother. Throughout the "Monstruo" section, the Baby Lollipops case and the part of Díaz's childhood where she lives with her mother are intertwined. We cannot examine one without referencing the other. This story has become inexplicably tangled within the web of Díaz's life. This is especially clear through the craft of this part of the story—the way every new detail about the Baby Lollipops case makes its way into the novel, the way time is defined in reference to the case ("years before they'd found the baby" (74), "the spring after they found the body" (84), etc.) both suggest that Díaz's childhood cannot be separated from the case. As she's drawing larger factual conclusions about the case, she's also drawing conceptual conclusions about the case, and about herself. She's incorrectly taught that "being a lesbian was part of the crime" (80), and correctly learns that "there comes a time when we realize that our parents cannot protect us" (83). Both of these concepts—sexuality and the movement away from parents as one grows older—are huge themes throughout the rest of the book that Díaz could not explore without introducing the way they originally enter the story: through her understanding of the Baby Lollipops case.

One of the last times Baby Lollipops makes an appearance in the story is when Díaz is much older. Dressed as a teenage version of herself, Díaz "stuffed [her] pocked with Charms Blow Pops and Ring Pops" (280) as a way to physically represent how much of her consciousness was devoted to the Baby Lollipops case. Yet, "every Halloween [since Lázaro died, she's] thought of him, all those lollipops in [her] pockets, how he'd be a man now" (281). Díaz cannot separate her curiosity of the Baby Lollipops case from her childhood self, and admits that even as an adult, part of her consciousness cannot fully separate from the case. Díaz continues to let the Baby Lollipops case affect her understanding of the world. She defines her teenage self not only as a hood girl, but as the hood girl who also followed this murder case closely. Díaz's early curiosity about the story, the way the media wouldn't let her forget about Baby Lollipops, caused her to adopt the story as part of who she is.

Díaz has interacted with many different stories, as evidenced throughout her memoir, and they have each affected her in different ways. Her interaction with the Baby Lollipops story only gives us one answer to the question of what we do with the stories we cannot escape.

*This response can also be found on my Goodreads page*

Comments

Post a Comment